Not long ago I watched a pair of late 1930s films featuring iconic names, Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. I know what you're thinking, but you're wrong although one of the movies is monstrously awful. Both turned out to be locked room mysteries.

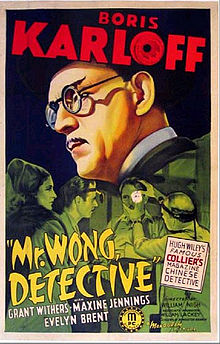

Mr. Wong, Detective (1938)

Mr. Wong, Detective (1938)This Karloff film is clever if you forgive a kind of police stereotype and the fact Karloff isn't Chinese, but it tied in with America's on-going fascination with the Orient.

I found myself smiling at a particular 'trope' (for lack of a better word), but discovered the plot hinges upon it. Given that wrinkle, the story turns out to be surprisingly satisfying. If you haven't seen it, it's worth watching.

As much as I like and recommend this film, I'll talk about another with a major failing.

Murder by Television (1935)

In contrast, the Lugosi flick was surprising awful. Bela himself seems resigned to struggling through the movie trying not to tatter his reputation.

In contrast, the Lugosi flick was surprising awful. Bela himself seems resigned to struggling through the movie trying not to tatter his reputation.What's not to like? It contains everything: corporate intrigue, high tech toys, a musical number, comic moments, and an imbecilic dénouement. Er, but wait, there's more: A half-hearted romantic flame flickers, sputters, and almost dies. Did they forget anything?

Movies in Black & White

The best part of Murder by Television was the cook, Hattie McDaniel, who stole the show with her gentle humor. I heard she sang in this film, though how and why remains a mystery– often films slipped in musical numbers on the flimsiest of excuses.

When I saw no singing, I shrugged it off until I came across a note in IMdb that suggested this particular print may have been intended for America's Deep South and deliberately omitted the scene.

What a shame. I can't imagine that Miss Hattie singing would have offended Southern sensibilities, so I'm still mystified if she sang in the film and if it was subsequently deleted. If you know details, share them in the comments. Meanwhile, back in the studio…

Television in 1935

A character in the film makes this prediction: "Television is the greatest step forward we have yet made in the preservation of humanity. It will make … a paradise we have always envisioned but never seen."

Presumably they were thinking of Dancing with the Stars and not Jerry Springer or 'rasslin' (which can be synonymous).

In the early years, television was a hot topic in radio enthusiast magazines. Numerous technical contributions from around the world– Russia, France, Mexico, Hungary, Scotland, the UK and US– led to an explosion of television invention in the mid-1920s.

By 1928, General Electric began experimental transmission from two stations in Schenectady and New York City, the figure of Felix the Cat rotating on a turntable. The Great Depression may have devastated the working man, but technical development continued.

Murder by Television was released in 1935 at a moment when the exciting possibilities of TV appeared poised on the threshold. The following year, Germany would broadcast the Olympic games from Berlin and Leipzig and by November, the BBC tele-vising group would begin the world's first public regular 'high definition' transmission from the Alexandra Palace in London.

In that context, the underpinnings of Murder by Television weren't out of place. The value of the props– actual experimental television on loan– was $75,000 for a film budgeted at $35,000. For those familiar with competing technologies, a close look reveals the mechanical rotating aperture that was one thrust of development at the time.

Reel Problem (spoiler)

| Professional Tip |

|---|

| First clue when writing a tech thriller: look up interstellar in the dictionary. Hey, I told you the plot was bad! |

I won't reveal the howdunit of Mr. Wong, but I'll spare you the drudgery of Murder by Television, not the who, but the how. (Trust me: The movie will gel your mind and you'll forget I told you.) The inventor was murdered by– are you ready– "the interstellar frequency death ray". Verily, I say unto you.

A Noir Treat

From my CB files, I tender this little noir film from the Bristol band Portishead, which perfectly captures the tone and mood of a late 60s spy film. Like many noir films, To Kill a Dead Man is more ambience than logic, but it's satisfying. Fortunately Beth Gibbons doesn't sing until the closing credits, leaving the viewer with a mellow Ipcress File melancholy. Granted she's not so bad here or in Catch the Tear as on other tracks that cause one to wonder why so many bands have their Yoko Ono.